If the Edge Again Bitterness Is Sweet if Missed the Hidden Love in the Hearts of

"God Speed" past Edmund Leighton

10 Greatest Love Poems Ever Written

by Conrad Geller

People are always asking "What are the all-time honey poems?" or "Where can I find something beautiful to say to the woman I beloved?" or "…to the human I beloved?"

If you are looking for dear poems in more modern linguistic communication, you volition probably detect the 10 All-time Honey Poems of 2021 useful. If you lot similar a more classical way, well, hither I am once more, unbowed by the heartfelt, sometimes urgent suggestions for altering my recent "10 Greatest Poems about Decease." This fourth dimension I choose a topic—beloved—less grim if equally compelling. These should quench your thirst for the best love poems, but don't take these as some kind of how-to manual in your relationship. Like death, love seems to be something almost poets know footling about; for evidence, run into their biographies. The poems I have called this time embrace the total spectrum of responses to honey, from joy to ache, and sometimes a mixture of both. Every bit befits the topic this time, the list is a flake heavy on Romantics and light on those rational Enlightenment types. Hither, with a few comments and no apologies, is the listing:

Related Content

10 All-time Love Poems of 2021

ten Greatest Poems Ever Written

x. "Since There'southward No Help," by Michael Drayton (1563-1631)

Information technology may be a bad augury to brainstorm with a poem past a loser, just there it is. Drayton, a contemporary and possible acquaintance of the Bard, evidently had come to the unhappy end of an affair when he penned this sonnet. He begins with a bear witness of stoic indifference: ". . . you get no more of me," but that tin can't last. In the final six lines he shows his true feelings with a series of personifications of the dying figures of Dearest, Passion, Faith, and Innocence, which he pleads tin can be saved from their fate by the lady's kindness.

Michael Drayton

.

Since There's No Help

Since at that place's no assistance, come let us kiss and part;

Nay, I accept done, you get no more of me,

And I am glad, yea glad with all my heart

That thus so cleanly I myself tin free;

Shake hands forever, cancel all our vows,

And when nosotros meet at whatever time once again,

Exist it not seen in either of our brows

That we one jot of former love retain.

Now at the last gasp of Love's latest breath,

When, his pulse failing, Passion speechless lies,

When Faith is kneeling by his bed of death,

And Innocence is closing up his eyes,

At present if thou wouldst, when all have given him over,

From death to life thou mightst him notwithstanding recover.

.

.

9. "How Do I Love Thee," past Elizabeth Barrett Browning (1806-1861)

If poetry, equally Wordsworth asserted, is "emotion recollected in tranquility," this sonnet scores high in the former essential but falls short of the latter. Elizabeth may take been the original arts groupie, whose passion for the famous poet Robert Browning seems to have known no limits and recognized no excesses. She loves she says "with my babyhood's organized religion," her dearest now holding the place of her "lost saints." No wonder this verse form, whatever its hyperbole, has long been a favorite of adolescent girls and matrons who remember what it was like.

.

How Do I Honey Thee?

Browning

How do I love thee? Permit me count the ways.

I love thee to the depth and breadth and summit

My soul tin can reach, when feeling out of sight

For the ends of being and ideal grace.

I love thee to the level of every day'southward

Most tranquillity need, by sun and candle-calorie-free.

I love thee freely, as men strive for right.

I love thee purely, as they turn from praise.

I dearest thee with the passion put to utilise

In my quondam griefs, and with my babyhood's organized religion.

I dear thee with a love I seemed to lose

With my lost saints. I love thee with the jiff,

Smiles, tears, of all my life; and, if God choose,

I shall but love thee improve after death.

.

.

8. "Honey's Philosophy," past Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792-1822)

In spite of its title, this very sweet sixteen-line poem has nothing to do with philosophy, equally far as I tin can see. Instead, it promulgates one of the oldest arguments of a young man to a maid: "All the earth is in intimate contact – water, wind, mountains, moonbeams, even flowers. What about you lot?" Since "Nothing in the world is single," he says with multiple examples, "What is all this sweet work worth / If 1000 kiss not me?" Interestingly, the lover'due south proof of the "law divine" of mingling delicately omits any reference to animals and their mingling behavior. In any case, I hope it worked for him.

Percy Bysshe Shelley

.

Dearest's Philosophy

The fountains mingle with the river

And the rivers with the ocean,

The winds of heaven mix for always

With a sweet emotion;

Nothing in the world is single;

All things by a law divine

In one spirit meet and mingle.

Why not I with thine?—

Encounter the mountains buss high heaven

And the waves clasp one another;

No sister-flower would be forgiven

If it disdained its brother;

And the sunlight clasps the earth

And the moonbeams kiss the sea:

What is all this sweet work worth

If 1000 kiss not me?

.

.

7. "Honey," by Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1772-1834)

Here we have some other bold attempt at seduction, this i much longer and more complicated than Shelley's. In this poem, the lover is attempting to proceeds his want by highly-seasoned to the tender emotions of his object. He sings her a song nearly the days of chivalry, in which a knight saved a lady from an "outrage worst than death" (whatever that is), is wounded and eventually dies in her artillery. The poet's dearest, on hearing the story, is deeply moved to tears and, to make the story non as long as the original, succumbs.

Equally with his most famous poem, "The Rime of the Ancient Mariner," Coleridge employs the oldest of English forms, the carol stanza, but hither he uses a lengthened second line. Coleridge, past the way, could actually tell a romantic story, whatever his ulterior motives.

.

Dearest

Coleridge

All thoughts, all passions, all delights,

Any stirs this mortal frame,

All are but ministers of Beloved,

And feed his sacred flame.

Oft in my waking dreams do I

Live o'er again that happy hour,

When midway on the mountain I lay,

Beside the ruined belfry.

The moonshine, stealing o'er the scene

Had blended with the lights of eve;

And she was at that place, my hope, my joy,

My ain dear Genevieve!

She leant against the arméd man,

The statue of the arméd knight;

She stood and listened to my lay,

Amid the lingering lite.

Few sorrows hath she of her own,

My promise! my joy! my Genevieve!

She loves me best, whene'er I sing

The songs that make her grieve.

I played a soft and doleful air,

I sang an erstwhile and moving story—

An old rude song, that suited well

That ruin wild and hoary.

She listened with a flitting blush,

With downcast eyes and modest grace;

For well she knew, I could not cull

Only gaze upon her face.

I told her of the Knight that wore

Upon his shield a burning brand;

And that for ten long years he wooed

The Lady of the Land.

I told her how he pined: and ah!

The deep, the low, the pleading tone

With which I sang some other's dear,

Interpreted my own.

She listened with a flitting chroma,

With downcast eyes, and modest grace;

And she forgave me, that I gazed

Too fondly on her face!

Simply when I told the barbarous scorn

That crazed that bold and lovely Knight,

And that he crossed the mountain-woods,

Nor rested day nor night;

That sometimes from the fell den,

And sometimes from the darksome shade,

And sometimes starting up at in one case

In light-green and sunny glade,—

In that location came and looked him in the confront

An angel beautiful and bright;

And that he knew it was a Fiend,

This miserable Knight!

And that unknowing what he did,

He leaped amidst a murderous band,

And saved from outrage worse than decease

The Lady of the Land!

And how she wept, and clasped his knees;

And how she tended him in vain—

And ever strove to expiate

The scorn that crazed his encephalon;—

And that she nursed him in a cave;

And how his madness went away,

When on the yellow woods-leaves

A dying human being he lay;—

His dying words—simply when I reached

That tenderest strain of all the ditty,

My faultering voice and pausing harp

Disturbed her soul with pity!

All impulses of soul and sense

Had thrilled my guileless Genevieve;

The music and the doleful tale,

The rich and balmy eve;

And hopes, and fears that kindle hope,

An undistinguishable throng,

And gentle wishes long subdued,

Subdued and cherished long!

She wept with pity and delight,

She blushed with love, and virgin-shame;

And similar the murmur of a dream,

I heard her exhale my name.

Her bosom heaved—she stepped aside,

As conscious of my look she stepped—

Then suddenly, with timorous heart

She fled to me and wept.

She half enclosed me with her arms,

She pressed me with a meek cover;

And bending dorsum her caput, looked up,

And gazed upon my confront.

'Twas partly dear, and partly fear,

And partly 'twas a bashful fine art,

That I might rather feel, than meet,

The swelling of her heart.

I calmed her fears, and she was at-home,

And told her love with virgin pride;

And so I won my Genevieve,

My bright and beauteous Bride.

.

.

6. "A Ruddy, Red Rose," by Robert Burns (1759-1796)

Burns' all-time-known poem besides "Auld Lang Syne" is a elementary declaration of feeling. "How beautiful and delightful is my love," he says. "You are so lovely, in fact, that I will honey you to the end of fourth dimension. And even though we are parting now, I will render, no thing what." All this is expressed in a breathtaking excess of metaphor: "And I volition love thee withal, my dear, / Till a' the seas gang dry out." This poem has no peer equally a simple weep of a young man who knows no boundaries.

Robert Burns

.

A Red, Red Rose

O my Luve is like a scarlet, crimson rose

That'south newly sprung in June;

O my Luve is like the tune

That's sweetly played in melody.

So fair art thou, my bonnie lass,

So deep in luve am I;

And I will luve thee still, my dear,

Till a' the seas gang dry.

Till a' the seas gang dry, my dear,

And the rocks melt wi' the sun;

I will love thee nonetheless, my dear,

While the sands o' life shall run.

And fare thee weel, my but luve!

And fare thee weel awhile!

And I volition come once more, my luve,

Though it were x k mile.

.

.

v. "Annabel Lee," past Edgar Allan Poe (1809-1849)

Poe shows off his astonishing talent in the manipulation of language sounds here, perhaps his best-known poem after "The Raven." It'due south a festival of auditory effects, with a delightful mixture of anapests and iambs, internal rhymes, repetitions, assonances. The story itself is a Poe favorite, the tragic death of a beautiful, loved girl, died after her "high-built-in kinsman" separated her from the lover.

.

Edgar Allan Poe

Annabelle Lee

It was many and many a year ago,

In a kingdom by the sea,

That a maiden in that location lived whom you lot may know

By the name of Annabel Lee;

And this maiden she lived with no other thought

Than to beloved and exist loved by me.

I was a child and she was a child,

In this kingdom past the bounding main:

But we loved with a love that was more than beloved—

I and my Annabel Lee;

With a love that the winged seraphs of heaven

Laughed loud at her and me.

And this was the reason that, long ago,

In this kingdom by the sea,

A wind blew out of a cloud, chilling

My beautiful Annabel Lee;

So that her blue-blooded kinsman came

And diameter her away from me,

To shut her up in a sepulchre

In this kingdom by the bounding main.

The angels, not half so happy in heaven,

Went laughing at her and me—

Yes!—that was the reason (equally all men know,

In this kingdom by the ocean)

That the wind came out of the cloud past dark,

Chilling and killing my Annabel Lee.

But our love it was stronger past far than the love

Of those who were older than nosotros—

Of many far wiser than we—

And neither the laughter in sky above,

Nor the demons downward under the sea,

Can always dissever my soul from the soul

Of the beautiful Annabel Lee:

For the moon never beams, without bringing me dreams

Of the beautiful Annabel Lee;

And the stars never ascension, but I feel the brilliant eyes

Of the cute Annabel Lee;

And then, all the night-tide, I lie down by the side

Of my darling—my darling—my life and my bride,

In her sepulchre there by the body of water,

In her tomb past the sounding sea.

.

.

4. "Whoso List to Hunt," by Sir Thomas Wyatt (1503-1542)

Supposedly written about Anne Boleyn, wife of King Henry VIII, this bitter verse form compares his beloved to a deer fleeing earlier an exhausted hunter, who finally gives upwardly the chase, considering, equally he says, "in a net I seek to concur the wind." As well, he reflects, she is the king's holding, and forbidden anyway. The bitterness comes mainly in the first line: "I know where at that place is a female deer, if anyone wants to go after her." Some of the tougher vocabulary is translated below. As the history goes, she could non produce the male heir Henry wanted and he (probably) wrongfully defendant her of incest and adultery but so he could accept her executed. This dearest, hijacked by college forces, painfully elusive, and wildly tempting is exquisitely real and compelling.

.

Whoso List to Hunt

Wyatt

Whoso listing to hunt, I know where is an hind,

Simply every bit for me, alas, I may no more than.

The vain travail hath exhausted me so sore,

I am of them that uttermost cometh backside.

Yet may I by no ways my wearied heed

Draw from the deer, only as she fleeth afore

Fainting I follow. I leave off therefore,

Since in a net I seek to hold the air current.

Who list her hunt, I put him out of doubt,

As well as I may spend his time in vain.

And graven with diamonds in messages plain

In that location is written, her fair cervix round most:

"Noli me tangere, for Caesar's I am,

And wild for to hold, though I seem tame."

Whoso list: whoever wants

Hind: Female person deer

Noli me tangere: "Don't bear on me"

.

.

3. "To His Coy Mistress," by Andrew Marvell (1621-1678)

Yet some other seduction endeavor in verse, perhaps this poem doesn't belong on a list like this, since it isn't about love at all. The lover is trying to convince a reluctant ('coy") lady to accede to his importuning, not by a sad story, as in the Coleridge poem, or by an appeal to nature, as in Shelley, but by a formal argument: Sexuality ends with decease, which is inevitable, so what are you lot saving it for?

. . . so worms shall try

That long preserved virginity,

And your quaint accolade turn to dust,

And into ashes all my lust.

and it ends with the pointed suggestion,

Let united states of america roll all our strength and all

Our sweetness up into one ball,

And tear our pleasures with crude strife

Thorough the atomic number 26 gates of life.

This is one of the ten best poems in the English language, so I'll include information technology hither, whether information technology can exist strictly pinned down with a label similar dear or death or not.

.

To His Coy Mistress

Marvell

Had we just world enough and time,

This coyness, lady, were no crime.

We would sit down down, and think which way

To walk, and laissez passer our long love's day.

Yard by the Indian Ganges' side

Shouldst rubies find; I by the tide

Of Humber would complain. I would

Love you lot ten years earlier the flood,

And you should, if y'all please, pass up

Till the conversion of the Jews.

My vegetable dear should grow

Vaster than empires and more slow;

An hundred years should go to praise

Thine eyes, and on thy brow gaze;

Two hundred to adore each breast,

Simply thirty thousand to the residuum;

An age at least to every part,

And the last age should show your heart.

For, lady, you deserve this state,

Nor would I love at lower rate.

But at my back I always hear

Time's wingèd chariot hurrying near;

And yonder all before us lie

Deserts of vast eternity.

Thy dazzler shall no more than be found;

Nor, in thy marble vault, shall sound

My echoing song; and then worms shall endeavor

That long-preserved virginity,

And your quaint honour plow to dust,

And into ashes all my lust;

The grave's a fine and individual place,

Merely none, I think, do there cover.

Now therefore, while the youthful hue

Sits on thy pare like morning dew,

And while thy willing soul transpires

At every pore with instant fires,

At present let us sport u.s.a. while we may,

And now, like amorous birds of prey,

Rather at once our time devour

Than languish in his slow-chapped power.

Let us coil all our strength and all

Our sweetness up into one brawl,

And tear our pleasures with rough strife

Through the fe gates of life:

Thus, though nosotros cannot make our sunday

Stand up nevertheless, nonetheless we volition brand him run.

.

.

2. "Bright Star," by John Keats (1795-1821)

Keats brings an most overwhelming sensuality to this sonnet. Surprisingly, the first eight lines are not virtually love or even man life; Keats looks at a personified star (Venus? Merely it's non steadfast. The North Star? It'due south steadfast just non peculiarly bright.) Any star it may exist, the sestet finds the lover "Pillow'd upon my fair love'due south ripening breast," where he plans to stay forever, or at least until expiry. Somehow, the surprising juxtaposition of the wide view of earth as seen from the heavens and the intimate picture of the lovers works to invest the scene of dalliance with a cosmic importance. John Donne sometimes accomplished this aforementioned event, though none of his poems made my final cut.

John Keats

.

Brilliant Star

Bright star, would I were stedfast every bit thou art—

Not in lone splendour hung aloft the dark

And watching, with eternal lids apart,

Like nature's patient, sleepless Eremite,

The moving waters at their priestlike task

Of pure ablution round world's human being shores,

Or gazing on the new soft-fallen mask

Of snow upon the mountains and the moors—

No—yet still stedfast, notwithstanding unchangeable,

Pillow'd upon my fair dearest's ripening chest,

To feel for ever its soft autumn and great,

Awake for ever in a sweetness unrest,

All the same, still to hear her tender-taken breath,

And then live ever—or else swoon to death.

.

.

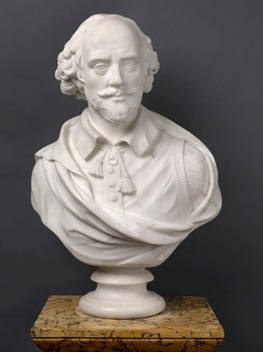

1. "Let Me Not to the Marriage of True Minds" (Sonnet 116), by William Shakespeare (1564-1616)

Shakespeare

This poem is not a personal entreatment but a universal definition of honey, which the poet defines as abiding and unchangeable in the face of any circumstances. Information technology is like the North Star, he says, which, even if we don't know anything else virtually it, we know where information technology is, and that's all nosotros need. Even death cannot lord itself over beloved, which persists to the end of time itself. The final couplet strongly reaffirms his delivery:

If this be error and upon me proved,

I never writ, nor no man e'er loved.

The problem is that if Shakespeare is right about beloved's constancy, so none of the other poems in this list would have been written, or else they're not actually nearly love. It seems Shakespeare may be talking most a deeper layer of beloved, transcending sensual attraction and intimacy, something more than akin to compassion or benevolence for your fellow man. In this revelation of the nature of such a strength, from which mutual love is derived, lies Shakespeare's genius.

.

Sonnet 116

Let me not to the matrimony of true minds

Admit impediments. Honey is not love

Which alters when it amending finds,

Or bends with the remover to remove.

O no! it is an e'er-fixed mark

That looks on tempests and is never shaken;

Information technology is the star to every wand'ring bawl,

Whose worth'due south unknown, although his top exist taken.

Love's not Time's fool, though rosy lips and cheeks

Within his bending sickle'south compass come;

Love alters not with his brief hours and weeks,

But bears it out fifty-fifty to the edge of doom.

If this be error and upon me proved,

I never writ, nor no human always loved.

.

Post your own best love poem selection or list in the comments section below.

.

.

Conrad Geller is an one-time, mostly formalist poet, a Bostonian now living in Northern Virginia. His piece of work has appeared widely in print and electronically.

Notation TO READERS: If you enjoyed this poem or other content, please consider making a donation to the Lodge of Classical Poets.

Notation TO POETS: The Society considers this page, where your poesy resides, to be your residence as well, where you may invite family unit, friends, and others to visit. Feel free to treat this page as your home and remove anyone here who disrespects you. Only transport an email to mbryant@classicalpoets.org. Put "Remove Comment" in the subject line and list which comments you would like removed. The Lodge does not endorse any views expressed in individual poems or comments and reserves the right to remove whatsoever comments to maintain the decorum of this website and the integrity of the Gild. Please run across our Comments Policy hither.

CODEC News:

Source: https://classicalpoets.org/2016/10/27/10-greatest-love-poems-ever-written/

0 Response to "If the Edge Again Bitterness Is Sweet if Missed the Hidden Love in the Hearts of"

Post a Comment